Poems of the Revolution

Spirituality and the Freedom in Dionysios Solomos’ Poems “The Hymn to Liberty” and “The Free Besieged”

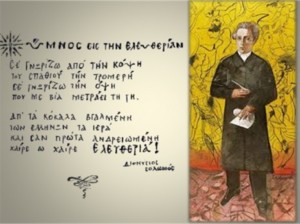

Dionysios Solomos, who is widely acknowledged as the national poet of Greece, was born on April 8, 1798 on the island of Zakynthos. From a young age he immersed himself in the life of the Church and yearned for the Independence of his country. The religiosity in Solomos’ work is so prevalent and incessant that it can hardly go unnoticed. His poems include many religious ideas, images, expressions, events and persons, both biblical and historical. Two outstanding poems that constitute an integral part of the Greek psyche and show the poet’s intrinsic nature are “The Hymn to Liberty” and the “The Free Besieged”. These two poems which were written approximately 200 years ago, inspired by the events of the Greek Revolution of 1821, are highly regarded and express what every Greek soul recognises when they hear the word “ελευθερία” (freedom).

“The Hymn to Liberty” is a landmark poem which praises the struggle of the Greeks and provides an insight into Solomos’ character showing that, apart from being an advocate of the Greek nation’s struggle for freedom, he also had a deep religious faith. This poem was written in 1823 and it highlights the significance of freedom to the Greek cause. The Greeks had yearned for their autonomy since 1453 and this is revealed by the fact that there were 123 failed attempts at gaining independence from the Ottoman empire prior to 1821. The more they were suppressed, the harder the Greek nation struggled for its freedom, yet all this was done within the framework of their Orthodox faith. The author of the poem salutes the personified image of Freedom and exhorts the Greek people to continue fighting for both their freedom and faith. Rudyard Kipling’s noteworthy translation conveys the atmosphere of Solomos’ demotic Greek.

There are a number of historical events which are covered by “The Hymn to Liberty”, which also happens to be the lon

gest national anthem in the world, containing 158 verses. These include the Fall of Tripolitsa (23 September 1821) which was the Turkish stronghold of the Peloponnese, the Greek victory at the Battle of Dervenakia (26 – 28 July 1822), the first Siege of Mesolongi (25 October – 31 December 1822), a number of naval engagements, including the burning of the Turkish flagship near Tenedos (November 1822), as well as the Hanging of Patriarch Gregory V, on Easter Sunday, 1821. The poem encaptulates all these events because they show the faith, the courage, the determination and the resolution that the Greeks possessed in the lead up to, and during the early years of, the Greek Revolution. Solomos completes the poem advising the Greek fighters to unite and stop the internal strife and discord that had started developing within the ranks.

Solomos’ emphasis of the spiritual dimension of “The Hymn to Liberty” is shown in the following extract, where both the value of the faith and the homeland to the Greek fighters is expressed. Religion becomes the guide and standard-bearer of the Greek struggle and the most sacred of Christian symbols, the Cross, becomes once again the defender of the Christian world. This is reminiscent of Constantine the Great raising the Cross of Christ at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge.

Solomos’ masterpiece “The Free Besieged” discusses the struggles of the defenders of the city of Mesolongi, who succeeded in holding their city for an entire year despite their numerical inferiority, and lack of food and supplies. In the end, they decided to make one last desperate attempt at freedom, a heroic exodus. So, on April 10, 1826, they opened the gates of the city and every last person inside the city came out to fight one last battle, in hopes that the women and children would manage to escape. “The Free Besieged” does not have a continuous narrative but consists of a series of scenes and glimpses that occurred during the last days of the siege of Mesolongi. One of the most well-known passages of this poem includes:

“Utter quiet of a tomb over the plain reigns. A chirping bird takes a seed & the poor mother complains. Hunger has darkened their eyes but on them she swears. A brave Souliot stands apart and his misery bears. “Why am I holding you my poor blackened musket You are a burden now to me, and the Saracen knows it.”

The goal of the besieged must be the conquest not of life but of moral and spiritual freedom. It is the enormity of their final decision that will lead them to death but also give them moral attainment. As a matter of fact, they were besieged, but on a spiritual level, their soul remained untamed, free, something that was amply demonstrated by the heroic exit of Mesolongi to avoid slavery. The essence for Solomos is this: the body may be perishable and overcome by hardships; but what is unbreakable and remains unchanged and untamed is the spirit and the limitless psychic powers of man, and this is what elevates the heroes of Mesolongi to sacred symbols of all Greece.

Solomos’ legacy has left us many characteristics to be proud of. Even though he was raised in a foreign environment and Italian was his first language, he came to appreciate the value of the Greek language to such an extent that at 25 years of age he wrote a hymn that became and still is the national anthem of both Greece and Cyprus. He grew up in the Church and read the Bible often. Although he was not appreciated during his lifetime, many of the giants of modern Greek poetry show great respect towards his achievements. “That is why the years and times will pass and the Muse will build temples in Greece and will find more pure and more worthy, more famous ministers and even Solomos will stand on the top … ”, as Palamas said. But also our Nobel Prize-winning poet Elytis is not wrong to suggest:

“Wherever evil finds you, brothers, wherever your minds are clouded, you remember Dionysius Solomos and remember Alexander Papadiamantis. The lily that knows no lies will rest the face of martyrdom with the little tincture of the glaucus on his lips.” (Elytis “Axion Esti”)

Source: Lychnos October 2021 / November 2021